What Happens During Primary Wastewater Treatment

What Happens During Primary Wastewater Treatment?

Wastewater treatment is an essential process in modern municipalities aimed at protecting public health and the environment from the harmful effects of untreated sewage. It involves several stages, each playing a crucial role in cleaning the water before it is returned to natural bodies like rivers, lakes, or oceans. The process is generally divided into primary, secondary, and tertiary treatment phases, each progressively removing contaminants. This article will focus on the intricacies of primary wastewater treatment, exploring its purpose, processes, technologies involved, and its significance in the broader context of water treatment.

Understanding Wastewater

Before diving into the specifics of primary wastewater treatment, it’s vital to understand what constitutes wastewater. Wastewater is any water that has been adversely affected in quality by human influence, including domestic, industrial, and storm wastewater. Domestic wastewater includes water from kitchens, bathrooms, and laundry sources, that contains a wide array of dissolved and suspended impurities like organic matter, nutrients, pathogens, and chemicals.

Industrial wastewater, on the other hand, may contain pollutants specific to the industrial processes from which it originates. Stormwater, resulting from precipitation events, can carry a variety of contaminants washed off from roads, agricultural lands, and urban areas. Primary treatment is crucial for addressing the physical characteristics of these types of wastewater and setting the stage for further treatment processes.

The Purpose of Primary Wastewater Treatment

The primary purpose of primary wastewater treatment is to remove materials that will either settle or float. This step is also crucial for reducing the biochemical oxygen demand (BOD) and total suspended solids (TSS) in the water, which, if left untreated, can lead to severe environmental harm. BOD is a measure of the amount of oxygen required by microorganisms to decompose organic matter in water. High BOD in wastewater can deplete the oxygen in receiving waters, adversely affecting aquatic life.

Similarly, TSS measures particles suspended in water and can include organic matter and inorganic substances. High levels of TSS can reduce light penetration in water, harming photosynthetic aquatic plants and organisms and leading to ecological imbalances. The primary treatment phase seeks to alleviate these concerns by removing approximately 30-50% of the BOD and up to 60% of the TSS, making it a crucial first step in the wastewater treatment process.

Key Processes in Primary Wastewater Treatment

1. Screening

The very first step in primary wastewater treatment is screening. This process involves passing the wastewater through bar screens to remove large solid objects such as sticks, rags, leaves, plastics, and other debris that could clog or damage the subsequent treatment equipment.

There are generally two types of screens: coarse and fine. Coarse screens typically have larger openings, about 20 to 50 mm, and are used to remove large debris. Fine screens have smaller openings, typically around 1.5 to 6 mm, and capture smaller particles that the coarse screens might miss. This initial screening is vital to protect downstream processes and equipment from potential damage and inefficiencies.

2. Grit Removal

After screening, the next step often involves grit removal. Grit consists of sand, gravel, cinders, or other heavy solid materials that are not organic in nature. These materials can cause significant wear and abrasion damage to pumps and other equipment if not removed.

Common methods to remove grit include aerated grit chambers and vortex-type grit removal systems. In an aerated chamber, air is introduced to create a spiral motion, allowing grit to settle at the bottom due to its weight while lighter organic matter remains in suspension. Vortex-type systems create a similar spiraling motion, using the centrifugal force to settle grit.

3. Sedimentation or Clarification

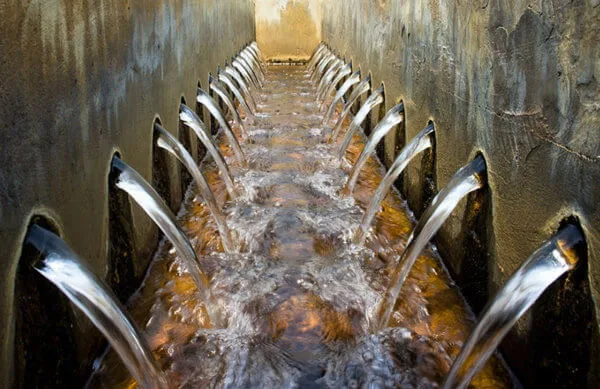

One of the most critical processes in primary treatment is sedimentation. This process involves allowing the wastewater to remain in large tanks, known as primary clarifiers or settling tanks, where gravity helps to settle out heavier suspended particles from the water. These particles form a sludge blanket at the bottom of the tank.

Primary clarifiers are typically designed to allow wastewater to remain undisturbed for several hours, enabling effective settling. The clarified water, now substantially free of heavy solids, continues to the next treatment phase. The settled solids, known as primary sludge, are collected at the bottom and later treated or disposed of separately.

4. Skimming

Simultaneously with sedimentation, skimming occurs at the surface of the clarifiers to remove floating materials such as oil, grease, and other light debris. These materials rise to the surface and are removed by mechanical skimmers, which sweep the surface and direct them to a separate collection area for further treatment.

Skimming is an essential process to prevent these materials from moving to the subsequent treatment stages where they could create operational issues and affect treatment efficiency.

Technologies in Primary Wastewater Treatment

Primary Clarifiers

Primary clarifiers are the core technology used in primary treatment. These enormous tanks are designed to optimize the time wastewater remains in them, allowing maximal settling of solids. The design of these tanks varies, including rectangular and circular configurations, each offering certain advantages.

Rectangular clarifiers have a plug-flow design that provides a uniform flow path, reducing short-circuiting and providing consistent performance. Circular clarifiers, meanwhile, offer structural advantages and are often easier to clean as they allow sludge to be pushed centrally before removal.

Automated Bar Screens

Modern bar screens are often fully automated, integrating sensors and controls to adjust the screening process according to the volume and type of incoming waste. These systems can improve the efficiency of debris removal and reduce labor costs.

Grit Removal Systems

Advanced grit removal systems, like vortex grit removal units, offer significant improvements over older technologies by combining efficiency in grit separation with energy savings. These systems are compact, require less maintenance, and offer precise removal of fine grit.

Importance and Challenges of Primary Wastewater Treatment

Environmental and Public Health Benefits

Primary wastewater treatment provides substantial environmental and public health benefits. By removing large solids, reducing BOD, and lowering TSS levels, it prevents the pollution of natural bodies of water, protects aquatic ecosystems, and reduces the load on secondary and tertiary treatment processes. Reduced BOD levels mean less oxygen consumption in the receiving waters, which is crucial for the survival of aquatic life.

Additionally, by removing pathogens tied up with particulate matter, primary treatment plays a role in reducing the spread of waterborne diseases, thus safeguarding public health.

Challenges and Limitations

Despite its importance, primary treatment is not without its challenges and limitations. One significant limitation is its inability to remove dissolved pollutants effectively. Organic and inorganic dissolved materials, including heavy metals and nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus, largely remain in the effluent after primary treatment and require further treatment.

Operational challenges also include handling the primary sludge, which requires careful management to avoid odors and potential environmental hazards. Primary treatment utilities must also optimize for varying wastewater compositions that result from different weather events or industrial discharges that introduce variability into the treatment process.

Conclusion

Primary wastewater treatment is a critical first step in the multi-stage process of treating wastewater. By efficiently removing large solids, grit, and floating debris, and significantly reducing BOD and TSS, it sets the stage for more advanced treatment processes that tackle finer pollutants. Its role in protecting both environmental and public health cannot be overstated, despite challenges and limitations that necessitate ongoing innovation and efficient management practices. With careful design and operation of primary treatment systems, we can ensure that wastewater treatment is not only more effective but also more adaptive to our growing and changing communities’ needs.